Musings

an Online Journal of Sorts

By Alyce Wilson

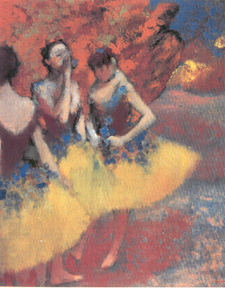

The Degas and the Dance exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art was so incredibly popular they had to let people in gradually to try to alleviate the crowding. Even so, you had to inch along the wall, being patient, waiting for your chance to look at the works.

The museum had handed out an audio tour, an electronic device where you would punch in the number of what you wanted to listen to. There was both an adult and a child tour, and I was listening to both, just to see how they were different. In some cases they had slightly different information.

The exhibit featured sketches and studies as well as finished works, including a computer program that allowed you to "flip through" his notebook. It was fascinating, this glimpse into his process. For example, despite the loose nature of his drawings, he would often plot quadrants to guide his drawings and ensure proper proportions.

His

most famous sculpture, "Little Dancer, Aged 14," was displayed

in its own small room. People gathered around on every side, some of them

unconsciously adopting her pose, one foot in front, hands clasped in back,

head tilted up to look at the sculpture.

His

most famous sculpture, "Little Dancer, Aged 14," was displayed

in its own small room. People gathered around on every side, some of them

unconsciously adopting her pose, one foot in front, hands clasped in back,

head tilted up to look at the sculpture.

Especially after leaving the exhibit and checking out other parts of the museum, you could see how radical his paintings were: they were not idealized depictions of either women or dancers. Edgar Degas (1834-1917) frequently depicted dancers in the process of completing a move, not having quite pulled into the final position. And since he spent time at dance schools and watched real students, the reason some of his dancers look more awkward is because their real-life models were. The youngest students would not have achieved the full grace of the older dancers.

You can really see how aware he was of how the body moves when you look at his sketches, especially some from the later years when he was posing nude models in positions similar to those from his paintings. You can really see what the body does in that position. As loose and free as these drawings may appear to be, they are careful studies of the real forms of the human body, not idealized in any way. It's not surprising that eventually, with his later works, layered with color, freer in their lines, that he would be an inspiration to the young artists of the time and would be considered a forerunner to Impressionism.

Movement was what Degas was about, in many ways. He wasn't interested in something that was posed. He wanted a split second of life, frozen in space with all its flaws and beauty. You have to remember that he was painting at the dawn of photography. And especially when Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) came along and, with his photographic motion studies, broke down movements, including those of a dancer turning, you can see that's what Degas was interesting in doing. He didn't want the frame at the end of the spin: he wanted the frame halfway through it.

The exhibit also featured supplementary material such as paintings and photographs that others had done, featuring the dancers of that time. One of the interesting things about these materials was to discover the dancers at the time were not at all like the dancers we see today. They didn't have the tiny, delicate body types we associate today with ballet. Instead, they looked like ordinary women, with highly developed legs! My guess is that the desired body type changed, first of all, when choreographers began to incorporate more lifts, where a male dancer would lift or spin a female ballerina. And then, of course, there are the changing social standards of the 20th Century. And third, as dancers began to wear modern, elasticized costumes, it would be considered more important for the entire body to be toned.

It was fascinating how many little girls were at the exhibit, and relatively few boys. As if the boys couldn't appreciate these exquisite drawings and paintings -- by a man -- simply because they were boys. Yet, it was okay for grown men to attend the exhibit. Perhaps I'm reading too much into this. Perhaps there were more boys than I had noticed but they just weren't the ones clapping their hands with glee, making themselves more noticeable.

Looking at the exhibit brought back memories of eight years of ballet classes, and how I used to read books like Noel Streatfeild's series ("Ballet Shoes," "Dancing Shoes" and "Theater Shoes") and marvel at the commitment it would take to build on dancing talent. I knew that I'd never be a prima ballerina. In a Degas painting, I would have been one of the girls on the sidelines, hiking up her stockings. But as far as Degas was concerned, that was beautiful, too. And looking at his works, you realize he was right.

Other

thoughts on the Philadelphia Art Museum:

January

14, 2003 - Museum Hijinks

You don't have to be perfect to be beautiful.

Copyright

2003 by Alyce Wilson

What

do you think? Share your thoughts

at Alyce's message board (left button):

![]()

![]()